Rainer Fuchs:

Das Möbel steht davor und das Bild hängt darüber

Grundlegend für Thomas Jochers Arbeit ist die Beachtung der Tatsache, daß konventionelle Bilder, wie sie in Wohnungen an den Wänden hängen, nicht nur Geschichten bewahren und erzählen, sondern den Raum auch möblieren und mithin eine Ikonografie des praktischen Nutzens abseits ihrer spezifischen Bildinhalte entwerfen. Genauso wie umgekehrt die Möbel selbst sich aus ihrer Rolle der reinen Funktionalität flüchten, indem sie durch Dekor und Design den Status von Kunstgegenständen und die Repräsentanz von Stilen beanspruchen. An und für sich lassen sich etwa barocke Möbel  mit ihren prächtigen Stoffbezügen und ihrem ornamentalen Corpus als Symbiosen von Bildern in skulpturaler Verschränkung betrachten, deren Kunstcharakter sich noch erhöht, wenn ihre Inbesitznahme als Sammlerobjekte ihre gewöhnliche Beanspruchung als Sitze ersetzt. So begegnen sich ständig kunstvolle Gebrauchsgegenstände und einfach gebrauchte Kunstgegenstände und erzeugen jene Atmosphäre von Wohnlichkeit, in der sich der permanente Rollentausch und die Bespiegelung von Kunst und Leben, von komplexen Bedeutungen und banalen Funktionen vollzieht.

mit ihren prächtigen Stoffbezügen und ihrem ornamentalen Corpus als Symbiosen von Bildern in skulpturaler Verschränkung betrachten, deren Kunstcharakter sich noch erhöht, wenn ihre Inbesitznahme als Sammlerobjekte ihre gewöhnliche Beanspruchung als Sitze ersetzt. So begegnen sich ständig kunstvolle Gebrauchsgegenstände und einfach gebrauchte Kunstgegenstände und erzeugen jene Atmosphäre von Wohnlichkeit, in der sich der permanente Rollentausch und die Bespiegelung von Kunst und Leben, von komplexen Bedeutungen und banalen Funktionen vollzieht.

Wenn aber einmal das Bild als Ding an der Wand unter anderen Dingen erkannt wird, so ist dieser Umstand fortan Bestandteil der Bildbedeutung, also seines Inhaltes, ganz abgesehen davon, was sonst auf dem Bild noch dargestellt ist. Die narrative Komponente und die ikonografischen Details nicht als primären Gehalt zu betrachten bedeutet dann auch, vornehmlich den Inhalt des Ausgestelltseins und des Anbringens an der Wand zur Sprache zu bringen. Dies eröffnet aber auch die Möglichkeit nach der Gegenständlichkeit des von illuminierten Gegenständen befreiten Bildes zu fragen. Innerhalb dieses Prozesses der Vergegenständlichung bewegt sich auch Jochers Arbeit, um aber weder im Sinne einer linearen Entwicklung das Ende des Abbildens zu proklamieren, noch um die Malerei als Bildniskunst des Plagiierens der sogenannten Wirklichkeit zu benutzen. An dieser Stelle erscheint ein Exkurs zur Beziehungsgeschichte der Begriffe Bild und Objekt angebracht, um Jochers Position darin beschreiben zu können.

Der traditionellen Terminologie der Kunstgeschichte zufolge sind ungegenständliche Bilder solche, die keine wiedererkennbaren Gegenstände abbilden. In der Geschichte der Kunstkritik unseres Jahrhunderts gibt es eine bekannte Interpretationstradition, die besagt, daß durch den Verzicht der Malerei auf die sogenannte Wirklichkeitswiedergabe sich überhaupt erst die Selbstdarstellung des Mediums Malerei bzw. der malerischen Mittel als die genuine Krönung einer Kunstgattung vollziehen konnte. Clement Greenbergs hegelianischer Euphorie ist es zu verdanken, daß sich eine Entwicklungstheorie etablierte, derzufolge die Malerei - in einer angeblich von den Impressionisten losgetretenen Entwicklung der Befreiung des Pinselstriches von der Gegenstandsbeschreibung - im abstrakten Expressionismus und der Farbfeldmalerei der Amerikaner endlich zu sich selbst kommen konnte. Diese Konstruktion einer sich erfüllenden Geschichte fußte auf der Kritik eines am sogenannten Gegenständlichen und Erzählerischen orientierten Inhaltsbegriffes und mündete in die Überzeugung, daß die beste Malerei diejenige sei, die nichts als sich selbst bedeute. Frank Stella brachte für sich diese Ideen auf den Punkt: "My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there. It really is an object.....All I want anyone to get out of my paintings and all I ever get out of them, is the fact that you can see the whole idea without any confusion....What you see is what you see." 1) Als Parallelerscheinung dieses konsequent vorgetragenen Anspruches prägte auf seiten der Geschichtsschreiber die Nivellierung tradierter ikonografischer Modi und ihrer ikonologischen Analyse die Betrachtung der Vergangenheit. Die ersten unfreiwilligen Opfer einer Marginalisierung oder zumindest einseitigen, sowie die subversiven und kritisch-ikonologischen Komponenten von Bildinhalten eliminierenden Kunstgeschichtsschreibung waren die als Vorläufer der reinen Malerei vereinnahmten Impressionisten. Das sonntägliche Leben an den Ufern der Seine und die in den Straßen flanierenden Figuren als Bildsujets vermittelten jene Entspanntheit und Arglosigkeit inmitten eines irdischen Paradieses, die das formale Spiel der Pinselstriche inhaltlich nicht wesentlich zu stören schienen. Proteges der Abstraktion, wie beispielsweise Werner Haftmann schufen diesen Ansichten breite Resonanz: "Der ganze Lebensentwurf des Impressionismus zielt darauf, zu den modernen Tatsachen des Lebens bedingungslos Ja zu sagen, zeitgenössisch zu empfinden und zu der Natur in jenes freudige, optimistische Verhältnis zu treten,das den schönen Schimmer dieser Welt annahm und die unterliegenden Wirkkräfte der Natur ....als die freundlichen Diener des menschlichen Fortschritts empfand." "Nie hat es eine Kunst gegeben, die ein so freudiges, von allen Sinnen getragenes Einverständnis mit der erscheinenden Welt in all ihrer Gegenwärtigkeit bekundet.".2) War den Expressionisten noch die Seelenlosigkeit des Impressionismus ein Dorn im Auge, so war den Apologeten der reinen Form die vermeintliche Inhaltslosigkeit, d.h. die eindimensionale Sicht der Welt als "freundlicher Garten"3) bei den Impressionisten gerade recht.

Wie bereits Stellas Ausspruch über den angestrebten Objektcharakter des bemalten Bildes zeigt, war die als Portrait ihrer selbst interpretierte Malerei nur eine Variante in einem Prozeß der Bespiegelung und Reflexion, in dessen Verlauf schließlich das Ende des Bildes und seine Vergegenständlichung zum Objekt bzw. seine Ablöse durch das Objekt verkündet wurden. Von Malerei zu sprechen bedeutete schon Anfang der 60er Jahre einen einzigen Begriff auf allzu Heterogenes zu beziehen und somit die Differenzen und Abgrenzungen, wie sie etwa in der Auseinandersetzung der Minimalisten mit der von ihnen als traditionalistisch und humanistisch qualifizierten europäischen Zeitkunst zum Ausdruck kamen, zu übersehen. Im Versuch, der relationalen Kompositionsvorstellung der Europäer zu entgehen, haben Künstler wie  Frank Stella und Donald Judd die innerbildliche Relationalität in eine zwischen Bild und Raum verwandelt und damit den Begriff der Malerei durch jenen des Bildes ersetzt, das als Gebilde und Gegenstand sich in den Raum einschreibt, anstatt als Ort der Einschreibung selbst Raum zu imaginieren. Daß Definitionsfragen bezüglich qualitativer Kriterien in der Kunst auch mit quantitativer Logik zu regeln waren, hat Judd selbst demonstriert. Ein Bild mutierte für ihn dann zum Objekt an der Wand und hörte auf ein Bild zu sein, wenn das Maß seiner Tiefe jenes von Länge und Breite übertraf: ".. it. occured to me that the idea would work if the pieces were projected, and that the painting situation would be completely avoided if they projected more than they were wide, top to bottom."4) Das zum Objekt gequetschte Bild - stereometrisch und seriell bereinigt, von Leinwand auf Metall

Frank Stella und Donald Judd die innerbildliche Relationalität in eine zwischen Bild und Raum verwandelt und damit den Begriff der Malerei durch jenen des Bildes ersetzt, das als Gebilde und Gegenstand sich in den Raum einschreibt, anstatt als Ort der Einschreibung selbst Raum zu imaginieren. Daß Definitionsfragen bezüglich qualitativer Kriterien in der Kunst auch mit quantitativer Logik zu regeln waren, hat Judd selbst demonstriert. Ein Bild mutierte für ihn dann zum Objekt an der Wand und hörte auf ein Bild zu sein, wenn das Maß seiner Tiefe jenes von Länge und Breite übertraf: ".. it. occured to me that the idea would work if the pieces were projected, and that the painting situation would be completely avoided if they projected more than they were wide, top to bottom."4) Das zum Objekt gequetschte Bild - stereometrisch und seriell bereinigt, von Leinwand auf Metall  umgarderobiert in den sogenannten "stacks"- sowie das im Raum stehende, weil geknickte Bild, sind zwei Typen von Bildern bei Judd, die der Malerei entronnen sind und die man schließlich mit dem Objektbegriff bedachte.

umgarderobiert in den sogenannten "stacks"- sowie das im Raum stehende, weil geknickte Bild, sind zwei Typen von Bildern bei Judd, die der Malerei entronnen sind und die man schließlich mit dem Objektbegriff bedachte.

Von der Befreiung der Farbe im Impressionismus über ihre Selbstdarstellung in der Farbfeldmalerei bis zu ihrer Verschmelzung mit dem Objekt zum farbigen Ding wurde eine Argumentationslinie gezogen, deren ironische Verkehrung in jenem Ausspruch Stellas gipfelte, demzufolge die beste Malerei jene sei, die die Farbe so beläßt, wie sie auch in der Tube ist, also in ihrer ursprünglichen und unverbrauchten Form: "I knew a wise guy who used to make fun of my painting, but he didn´t like the Abstract Expressionists either. He said they would be good painters if they could keep the paint only as good as it is in the can. And that´s what I tried to do. I tried to keep the paint as good as it was in the can."5) Das quasi in die Tube zurückdefinierte Bild erscheint wie das Negativ des vom Objekt absorpierten Bildes. Beidemale vom Verschwinden bedroht, hat das Bild wie aus einem Versteck heraus zurückgeschlagen.

Denn eine Art Rückverwandlung eines Objektes in ein Bild hat bereits Pino Pascali mit seiner "Mauer des Schlafes" 1968 vorgenommen. Fernab minimalistischer und wahrnehmungspsychologisch fundierter Gegenstandsbefragung beschwor Pascali die Poesie der Materialien, zu denen neben den verwendeten Polstern auch die im Werktitel benutzte Sprache gehört. Er hielt sich an die Gegenstände, die es sowieso schon gibt. Wie sich die Worte im Sprechen und Schreiben als Zeichen und bloße Bausteine für Bedeutungen verschwenden, so gehen die einzelnen Polster in der Mauer, die sie bedeuten, auf. Als Gegenstände an einem Ding ergaben sie doch zugleich ein Bild, das noch dazu bemalt ist. Was sich zeigt ist aber kein Bild über Reales - im Sinne gemalter Illusion - sondern ein reales Ding, das uns die Illusion eines Bildes gibt. Zwar wölben sich die Polster in den Raum, aber doch nur um als Segmente eines poetischen Bildes sich ganz daraus zurückzuziehen. Die Auflösung und das Ende des Bildes durch das Objekt erwiesen sich also schon bei Pascali als eine umkehrbare und damit entwertete Formel. Die Geschichte hielt nie lineare Progressionen bereit, diese entstammen ihrer Interpretation, die selbst Bestandteil der Geschichte werden und damit ihrerseits zu Verwechslungen verleiten. Wann immer die Dinge auch entstanden sind, spätestens im Bewußtsein des Betrachters schieben sie sich synchron zusammen. Die Geschichte läuft auf und gerät in jenen Hinterhalt, von dem aus sie neu geschrieben und konstruiert werden kann. Das einst als progressive und kausale Abfolge gesehene Verhältnis von Bild und Objekt, bzw. vom Bild zum Objekt hat nicht nur zur Auflösung des Bildes, sondern auch zur Neustrukturierung seines Begriffes geführt. Die Dehnbarkeit beschreibt nicht nur die Natur der Begriffe, sondern eignet auch dem mit ihrer Hilfe Begriffenen. Das Bild hat sich also nicht nur im Objekt aufgelöst, sondern auch das Objekt als seinen Gegner in sich einverleibt und eine Existenz als Zwitterwesen beansprucht.

Denn eine Art Rückverwandlung eines Objektes in ein Bild hat bereits Pino Pascali mit seiner "Mauer des Schlafes" 1968 vorgenommen. Fernab minimalistischer und wahrnehmungspsychologisch fundierter Gegenstandsbefragung beschwor Pascali die Poesie der Materialien, zu denen neben den verwendeten Polstern auch die im Werktitel benutzte Sprache gehört. Er hielt sich an die Gegenstände, die es sowieso schon gibt. Wie sich die Worte im Sprechen und Schreiben als Zeichen und bloße Bausteine für Bedeutungen verschwenden, so gehen die einzelnen Polster in der Mauer, die sie bedeuten, auf. Als Gegenstände an einem Ding ergaben sie doch zugleich ein Bild, das noch dazu bemalt ist. Was sich zeigt ist aber kein Bild über Reales - im Sinne gemalter Illusion - sondern ein reales Ding, das uns die Illusion eines Bildes gibt. Zwar wölben sich die Polster in den Raum, aber doch nur um als Segmente eines poetischen Bildes sich ganz daraus zurückzuziehen. Die Auflösung und das Ende des Bildes durch das Objekt erwiesen sich also schon bei Pascali als eine umkehrbare und damit entwertete Formel. Die Geschichte hielt nie lineare Progressionen bereit, diese entstammen ihrer Interpretation, die selbst Bestandteil der Geschichte werden und damit ihrerseits zu Verwechslungen verleiten. Wann immer die Dinge auch entstanden sind, spätestens im Bewußtsein des Betrachters schieben sie sich synchron zusammen. Die Geschichte läuft auf und gerät in jenen Hinterhalt, von dem aus sie neu geschrieben und konstruiert werden kann. Das einst als progressive und kausale Abfolge gesehene Verhältnis von Bild und Objekt, bzw. vom Bild zum Objekt hat nicht nur zur Auflösung des Bildes, sondern auch zur Neustrukturierung seines Begriffes geführt. Die Dehnbarkeit beschreibt nicht nur die Natur der Begriffe, sondern eignet auch dem mit ihrer Hilfe Begriffenen. Das Bild hat sich also nicht nur im Objekt aufgelöst, sondern auch das Objekt als seinen Gegner in sich einverleibt und eine Existenz als Zwitterwesen beansprucht.

Thomas Jocher geht in seiner Arbeit, wie gesagt, dieser doppelten Natur des Bildes als Medium illusionierter Räume einerseits, sowie als Gegenstand an sich nach, wobei der Künstler aber nicht auf die Funktion des Darstellens verzichtet. Vom Bild als Körper, der auf den menschlichen Körper verweist und diesen fragmenthaft durch Formung und Färbung des Bildobjektes erinnert, bis zu den großformatigen neuen Bildern mit ihren suggestiven und suggerierten Perspektiven und Raumillusionen, die das Betrachten als eine Inbesitznahme des Körpers formulieren, entfaltet sich bei Jocher eine synchron in Fläche und Raum angelegte Topologie des Bildes.

Der Maler unterläuft in den frühen Arbeiten die akademisch trainierte Illusionsmalerei durch ins Zentrum gesetzte Rosetten - und Blütenformen, die wie Logos auf den Flächen sitzen und mit ihren einfachen geschwungenen Formen ein variables und sowohl multiplizierbares wie auch mutierbares Grundvokabular darstellen. Die dekorative Funktion von Bilderrahmen und Passepartout -Schablonen scheint sich in den floralen Logos buchstäblich in den Bildinhalt verwandelt zu haben. Die Figur der Schablone ist gleichsam ins Bild gesickert und leuchtet von dort als Thema hervor. Wenn Jocher außerdem einzelne Motive aus bekannten Gemälden - an denen er sein Handwerk

Der Maler unterläuft in den frühen Arbeiten die akademisch trainierte Illusionsmalerei durch ins Zentrum gesetzte Rosetten - und Blütenformen, die wie Logos auf den Flächen sitzen und mit ihren einfachen geschwungenen Formen ein variables und sowohl multiplizierbares wie auch mutierbares Grundvokabular darstellen. Die dekorative Funktion von Bilderrahmen und Passepartout -Schablonen scheint sich in den floralen Logos buchstäblich in den Bildinhalt verwandelt zu haben. Die Figur der Schablone ist gleichsam ins Bild gesickert und leuchtet von dort als Thema hervor. Wenn Jocher außerdem einzelne Motive aus bekannten Gemälden - an denen er sein Handwerk schulte - als pars-pro-toto in seine Bilder setzt, so gilt auch für sie die Begrifflichkeit des Schemas und der Schablone. Allein das Kopieren bekannter Gemälde gleicht einer Reproduktion des bereits durch unzählige Reproduktionen zu einem Zeichen seiner selbst deklarierten Originals. Das Detail eines Ganzen nachzumalen, bedeutet das bekannte Vorbild auf ein signifikantes Zeichen zu reduzieren, das in seiner isolierten Form, gerade weil es - aus dem Zusammenhang gerissen - seinen ursprünglichen Sinn verliert, zum Logo für das Ganze wird. Es entsteht ein ganz eigenes Bild, ein Original des Kopisten, das ein bezeichnendes Licht auf die stets fragmenthaften und durch Vorwegnahmen gefilterten Interpretationen alter Gemälde wirft. Man gelangt ja gewöhnlich nicht von den Originalen zu den Reproduktionen, sondern trifft vielmehr umgekehrt in den Museen auf jene Werke, die man bereits von Bildern kennt. Je öfter ein Bild reproduziert wird und je bekannter es ist, desto stärker prägt es sich als visuelles Signet in unser Bewußtsein und leistet damit einer Verschüttung und Nivellierung seiner eigenen komplexen ikonografischen und ikonologischen Strukturen Vorschub. Was man schon zu kennen meint, hat man längst aus den Augen verloren.

schulte - als pars-pro-toto in seine Bilder setzt, so gilt auch für sie die Begrifflichkeit des Schemas und der Schablone. Allein das Kopieren bekannter Gemälde gleicht einer Reproduktion des bereits durch unzählige Reproduktionen zu einem Zeichen seiner selbst deklarierten Originals. Das Detail eines Ganzen nachzumalen, bedeutet das bekannte Vorbild auf ein signifikantes Zeichen zu reduzieren, das in seiner isolierten Form, gerade weil es - aus dem Zusammenhang gerissen - seinen ursprünglichen Sinn verliert, zum Logo für das Ganze wird. Es entsteht ein ganz eigenes Bild, ein Original des Kopisten, das ein bezeichnendes Licht auf die stets fragmenthaften und durch Vorwegnahmen gefilterten Interpretationen alter Gemälde wirft. Man gelangt ja gewöhnlich nicht von den Originalen zu den Reproduktionen, sondern trifft vielmehr umgekehrt in den Museen auf jene Werke, die man bereits von Bildern kennt. Je öfter ein Bild reproduziert wird und je bekannter es ist, desto stärker prägt es sich als visuelles Signet in unser Bewußtsein und leistet damit einer Verschüttung und Nivellierung seiner eigenen komplexen ikonografischen und ikonologischen Strukturen Vorschub. Was man schon zu kennen meint, hat man längst aus den Augen verloren.

Die Diskrepanz zwischen dem dunklen Fond des Bildes und der gemalten Plastizität der Rosetten und altmeisterlichen Zitate eröffnet die Möglichkeit, die Flächigkeit des Bildes durch einen aufgemalten Widerspruch zugleich zu bestätigen und doch radikal zu unterlaufen. Ebenso wie durch die Verräumlichung zum plastisch gefüllten Bildkörper - als zweiter von Jocher praktizierten bildnerischen Strategie - hintergeht die Malerei der gerundeten, blüten- oder zellenförmig sich ausbreitenden Strukturen das Primat des flachen Bildes und deklariert das Betrachten als eine Vereinnahmung und Täuschung des Blickes. Die zur schematischen Rosette implodierte Ornamentik des Rahmens bildet nur eine Facette der Umstülpung von Rand und Inhalt, von Kontext und Bild. Eine weitere findet sich in den prall gefüllten plastischen Bildpolstern, an denen die gespannte und kostbar leuchtende Haut sich an den Rändern nicht nur wie von selbst zur plastischen Rosette wölbt, sondern darüber hinaus auch den Glanz verräumlichter Ornamente verströmt. Der Rahmen scheint sich zum Bild geschlossen zu haben und sich als bildfüllendes Thema vorzutragen, um zugleich aus dem Bild zu verschwinden.

Die Diskrepanz zwischen dem dunklen Fond des Bildes und der gemalten Plastizität der Rosetten und altmeisterlichen Zitate eröffnet die Möglichkeit, die Flächigkeit des Bildes durch einen aufgemalten Widerspruch zugleich zu bestätigen und doch radikal zu unterlaufen. Ebenso wie durch die Verräumlichung zum plastisch gefüllten Bildkörper - als zweiter von Jocher praktizierten bildnerischen Strategie - hintergeht die Malerei der gerundeten, blüten- oder zellenförmig sich ausbreitenden Strukturen das Primat des flachen Bildes und deklariert das Betrachten als eine Vereinnahmung und Täuschung des Blickes. Die zur schematischen Rosette implodierte Ornamentik des Rahmens bildet nur eine Facette der Umstülpung von Rand und Inhalt, von Kontext und Bild. Eine weitere findet sich in den prall gefüllten plastischen Bildpolstern, an denen die gespannte und kostbar leuchtende Haut sich an den Rändern nicht nur wie von selbst zur plastischen Rosette wölbt, sondern darüber hinaus auch den Glanz verräumlichter Ornamente verströmt. Der Rahmen scheint sich zum Bild geschlossen zu haben und sich als bildfüllendes Thema vorzutragen, um zugleich aus dem Bild zu verschwinden.

Das Faktum des mobiliaren Charakters als Rahmenthema des Bildes in Verbindung mit der Thematisierung des Rahmens selbst als Bestandteil des Bildinhaltes findet sich bekanntlich auch als zentrales Motiv im Werk Allan McCollums. Er hat den Platz des Bildes an der Wand mit dessen Ort innerhalb des kulturellen Selbstverständnisses - wovon eben auch unsere bebilderten Wohnungen Zeugnis geben - verglichen: "Ein Gemälde ist etwas, das sich häufig über der Couch befindet - und es war eben genau diese nüchterne Definition, die mir in dieser ganzen formalistischen Debatte fehlte. Die `Gesetzmäßigkeiten` der Malerei sind Gesetzmäßigkeiten der Welt schlechthin."6) Konsequenterweise bezeichnet McCollum seine Bilder als "Surrogate", die bloß ihre Rolle als Gemälde spielen und genau darin ihren Inhalt finden, ohne in Fortsetzung ikonografischer Traditionen spezifische Geschichten zu erzählen. In diesen "stummen" wie "blinden" und daher sich selbst besprechenden und bespiegelnden Bildern grenzen die Rahmen keine Darstellungen ein, sondern repräsentieren per se ein zum Bild gehörendes Motiv. Die durch das Bild und auf ihm zum Ausdruck kommende Funktion von Bildern allgemein läßt sich auch als Thema für Jochers Vorgehen veranschlagen. Doch die von McCollum inszenierte Selbstbezüglichkeit der Bilder findet bei Jocher eine Abweichung, die sich am Begriff und am Bild des Körpers als Assoziationsfigur orientiert.

Das Faktum des mobiliaren Charakters als Rahmenthema des Bildes in Verbindung mit der Thematisierung des Rahmens selbst als Bestandteil des Bildinhaltes findet sich bekanntlich auch als zentrales Motiv im Werk Allan McCollums. Er hat den Platz des Bildes an der Wand mit dessen Ort innerhalb des kulturellen Selbstverständnisses - wovon eben auch unsere bebilderten Wohnungen Zeugnis geben - verglichen: "Ein Gemälde ist etwas, das sich häufig über der Couch befindet - und es war eben genau diese nüchterne Definition, die mir in dieser ganzen formalistischen Debatte fehlte. Die `Gesetzmäßigkeiten` der Malerei sind Gesetzmäßigkeiten der Welt schlechthin."6) Konsequenterweise bezeichnet McCollum seine Bilder als "Surrogate", die bloß ihre Rolle als Gemälde spielen und genau darin ihren Inhalt finden, ohne in Fortsetzung ikonografischer Traditionen spezifische Geschichten zu erzählen. In diesen "stummen" wie "blinden" und daher sich selbst besprechenden und bespiegelnden Bildern grenzen die Rahmen keine Darstellungen ein, sondern repräsentieren per se ein zum Bild gehörendes Motiv. Die durch das Bild und auf ihm zum Ausdruck kommende Funktion von Bildern allgemein läßt sich auch als Thema für Jochers Vorgehen veranschlagen. Doch die von McCollum inszenierte Selbstbezüglichkeit der Bilder findet bei Jocher eine Abweichung, die sich am Begriff und am Bild des Körpers als Assoziationsfigur orientiert.

Die anthropomorphe Dimension der Verkörperung des Bildes - also das Spiel mit dem Begriff des Körpers - wird in jenen Objekten offensichtlich, die wie abstrahierte Torsi erscheinen und die durch Bemalung mit Inkarnatfarben auf die menschliche Haut als eine über das Fleisch gespannte, von Falten, Einschnürungen und Schwellungen gezeichnete Membran anspielen. Es liegt nahe, die Verkörperung des Bildes an das Bild des Körpers zu koppeln. So wird dem menschlichen Körper Referenz erwiesen, ohne ihn tatsächlich abzubilden, aber zugleich auch die Vergegenständlichung des Bildes betrieben, ohne seine Funktion des Darstellens von Anderem aufzugeben.

erscheinen und die durch Bemalung mit Inkarnatfarben auf die menschliche Haut als eine über das Fleisch gespannte, von Falten, Einschnürungen und Schwellungen gezeichnete Membran anspielen. Es liegt nahe, die Verkörperung des Bildes an das Bild des Körpers zu koppeln. So wird dem menschlichen Körper Referenz erwiesen, ohne ihn tatsächlich abzubilden, aber zugleich auch die Vergegenständlichung des Bildes betrieben, ohne seine Funktion des Darstellens von Anderem aufzugeben.

Wenn die Geschichte, ihre Ereignisse und Interpretationen immer nur von der Gegenwart aus bedacht und überdacht werden können, so erscheint es auch angemessen, das auf den ersten Blick Verschiedene auch zugleich zu erzeugen und vor Augen zu stellen. Während es bei den polsterartigen Bildern reicht, die Farbe gleichmäßig aufzutragen, weil das Spiel des Lichtes selbst für die Schattierungen sorgt und die plastische Form sich als Realität inkarniert, hilft auf der flachen Leinwand nur der Trick der Malerei, die bewußte Täuschung mit zureichenden Mitteln, die von Jocher nicht verhehlt, sondern in  der schier endlosen Wiederholung der immergleichen Formen drastisch verdeutlicht wird. Die bedrängende Nähe der prallen plastischen Formen und die durch Malerei suggerierte unendliche Ferne umschreiben gleichermaßen die Umgehung der Fläche und des referenzlosen, sich selbst genügenden Bildes. Sie setzen auf die Illusion des modulartig strukturierten Raumes, die das Betrachten in eine Vereinnahmung des Betrachters verwandeln. Denn die Bilder figurieren auch als Ausschnitte, als in der Fläche konstruierte Segmente räumlicher Trichter, die nicht nur den Blick ansaugen, sondern ihre imaginären Kraftfelder auch in den Raum stülpen. Wie weich ausgekleidete dunkle Höhlen, die dem Eindringenden jeglichen Maßstab verwehren, wo der Makro- mit dem Mikrokosmos identisch wird, vereinnahmen die Bilder gleichsam mit dem Blick auch den Körper des Betrachters.

der schier endlosen Wiederholung der immergleichen Formen drastisch verdeutlicht wird. Die bedrängende Nähe der prallen plastischen Formen und die durch Malerei suggerierte unendliche Ferne umschreiben gleichermaßen die Umgehung der Fläche und des referenzlosen, sich selbst genügenden Bildes. Sie setzen auf die Illusion des modulartig strukturierten Raumes, die das Betrachten in eine Vereinnahmung des Betrachters verwandeln. Denn die Bilder figurieren auch als Ausschnitte, als in der Fläche konstruierte Segmente räumlicher Trichter, die nicht nur den Blick ansaugen, sondern ihre imaginären Kraftfelder auch in den Raum stülpen. Wie weich ausgekleidete dunkle Höhlen, die dem Eindringenden jeglichen Maßstab verwehren, wo der Makro- mit dem Mikrokosmos identisch wird, vereinnahmen die Bilder gleichsam mit dem Blick auch den Körper des Betrachters.

Diese Vereinnahmung des Betrachters, seine "Einbeziehung" ins Bild und die Thematisierung des Betrachtens ist im Werk Jochers ein von Beginn an zentrales Motiv.  Neben der Wahrnehmung von Bildern als Mobiliar unter Möbeln benutzt er anfangs zur fotografischen Dokumentation seiner eigenen Bilder auch Fauteuils und Stühle, die er in Bildrichtung quasi als Angebot und Anweisung für den Betrachter postiert. Diese realen Requisiten figurieren nicht nur als Maßstäbe für die Bilder und als verkörperte Maßstäblichkeit des Betrachtens, sondern sie korrespondieren durch ihre Polsterungen und geschwungenen Leisten mit den Formen der zu betrachtenden Bilder. Ihre körpergerechte Gestalt impliziert das Subjekt des Betrachters, dessen Körper und seine Aktivität des Wahrnehmens der Bildkörper. Weil aber nicht nur die Sitze als Staffage dienen, sondern ihnen gegenüber auch die Bilder zu Staffagen des Betrachtens mutieren, bestimmt sich die Rolle des Betrachters als Teilnehmer eines Rollenspieles, das in die eingangs beschriebene inszenierte Verschleifung von Bild und Mobiliar als Rezeption dieses Verschleifungsprozesses immer schon eingeklinkt ist. Es liegt dabei nahe, die Rolle des Rezipienten mit jener des Konsumenten von Monitorbildern - also mit den auf ihn zukommenden und ihn durch Identifikationsfiguren vereinnahmenden Bildern - zu vergleichen. Ferner erinnert auch die modulartige Struktur der scheinbar endlos dublizier- und manipulierbaren Bildbausteine,ihre auf Postiv-Negativ- sowie Hell-Dunkel-Effekte replizierende binäre Natur an eine monitorgenerierte, uns mit Simulationen versorgende Bildwelt.

Neben der Wahrnehmung von Bildern als Mobiliar unter Möbeln benutzt er anfangs zur fotografischen Dokumentation seiner eigenen Bilder auch Fauteuils und Stühle, die er in Bildrichtung quasi als Angebot und Anweisung für den Betrachter postiert. Diese realen Requisiten figurieren nicht nur als Maßstäbe für die Bilder und als verkörperte Maßstäblichkeit des Betrachtens, sondern sie korrespondieren durch ihre Polsterungen und geschwungenen Leisten mit den Formen der zu betrachtenden Bilder. Ihre körpergerechte Gestalt impliziert das Subjekt des Betrachters, dessen Körper und seine Aktivität des Wahrnehmens der Bildkörper. Weil aber nicht nur die Sitze als Staffage dienen, sondern ihnen gegenüber auch die Bilder zu Staffagen des Betrachtens mutieren, bestimmt sich die Rolle des Betrachters als Teilnehmer eines Rollenspieles, das in die eingangs beschriebene inszenierte Verschleifung von Bild und Mobiliar als Rezeption dieses Verschleifungsprozesses immer schon eingeklinkt ist. Es liegt dabei nahe, die Rolle des Rezipienten mit jener des Konsumenten von Monitorbildern - also mit den auf ihn zukommenden und ihn durch Identifikationsfiguren vereinnahmenden Bildern - zu vergleichen. Ferner erinnert auch die modulartige Struktur der scheinbar endlos dublizier- und manipulierbaren Bildbausteine,ihre auf Postiv-Negativ- sowie Hell-Dunkel-Effekte replizierende binäre Natur an eine monitorgenerierte, uns mit Simulationen versorgende Bildwelt.

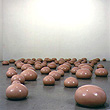

Die reale Einbeziehung ins Werk, d.h. die physische Umklammerung des Betrachters erfolgt in jenen Ausstellungssituationen, in denen entweder vom Künstler gestaltete  Bänke sich auch in ihrer Formung und Farbigkeit auf die Gemälde beziehen und die Fiktion des nach vorne gestülpten Raumes in einer Art realem Kondensat - den Bänken - bestätigen. Oder aber durch Vergegenständlichung der abstrakten Bildmodule in Form von prallen, hautfarbenen, in sich gesunkenen Kugelformen, verteilt auf dem Boden des Raumes. Die in den Weg gelegte Kunst ermöglicht uns die Reise innerhalb des Bildes, wenn man den Begriff hier noch beibehalten will. Sie verweist aber auch auf eine Struktur innerhalb des Oeuvres, das sich nie wirklich der Funktion des mimetischen Abbildens realer Vorbilder öffnet. Abbilden bedeutet bei Jocher die reflektierende Bezugnahme

Bänke sich auch in ihrer Formung und Farbigkeit auf die Gemälde beziehen und die Fiktion des nach vorne gestülpten Raumes in einer Art realem Kondensat - den Bänken - bestätigen. Oder aber durch Vergegenständlichung der abstrakten Bildmodule in Form von prallen, hautfarbenen, in sich gesunkenen Kugelformen, verteilt auf dem Boden des Raumes. Die in den Weg gelegte Kunst ermöglicht uns die Reise innerhalb des Bildes, wenn man den Begriff hier noch beibehalten will. Sie verweist aber auch auf eine Struktur innerhalb des Oeuvres, das sich nie wirklich der Funktion des mimetischen Abbildens realer Vorbilder öffnet. Abbilden bedeutet bei Jocher die reflektierende Bezugnahme einzelner Werkkomplexe aufeinander und wiederholt damit das in den einzelnen Werken erkennbare Szenario von Wiederholungen und Mutationen. Ein Motiv durchläuft die Medien der Kunst und generiert dabei verschiedene Typen von Bildern. Die am Boden liegenden, bemalten Gipskugeln sind als materialisierter Output einer Synthese der inkarnatfarbigen Bildkörper mit den malerisch imaginierten Kugelformen dechiffrierbar. So bewegt man sich zwischen den Kugeln zugleich auch innerhalb des Gesamtwerkes, dessen einzelne Komplexe man in der Überlegung verknüpft, ebenso wie man die einzelnen Kugeln zumgeschlossenen Werk rundet.

einzelner Werkkomplexe aufeinander und wiederholt damit das in den einzelnen Werken erkennbare Szenario von Wiederholungen und Mutationen. Ein Motiv durchläuft die Medien der Kunst und generiert dabei verschiedene Typen von Bildern. Die am Boden liegenden, bemalten Gipskugeln sind als materialisierter Output einer Synthese der inkarnatfarbigen Bildkörper mit den malerisch imaginierten Kugelformen dechiffrierbar. So bewegt man sich zwischen den Kugeln zugleich auch innerhalb des Gesamtwerkes, dessen einzelne Komplexe man in der Überlegung verknüpft, ebenso wie man die einzelnen Kugeln zumgeschlossenen Werk rundet.

Ganz aus der Nähe besehen verschleiert dieKugel dem Blick ihre Krümmung. Ihre Oberfläche wird zur Ebene und ihr Rand weitet sich zum Horizont. Für das Auge verlöscht dann ihre Form und man beginnt sie zu vergessen. So ein Bild der Kugel ergibt die Form einer Parabel, die man auch als Gleichnis auffassen kann, das an die Bilder an der Wand und ihr Verschwinden durch Annäherungen, d.h. durch Gewöhnung - etwa in Wohnungen an den Wänden - erinnert.

Für das Auge verlöscht dann ihre Form und man beginnt sie zu vergessen. So ein Bild der Kugel ergibt die Form einer Parabel, die man auch als Gleichnis auffassen kann, das an die Bilder an der Wand und ihr Verschwinden durch Annäherungen, d.h. durch Gewöhnung - etwa in Wohnungen an den Wänden - erinnert.

1) Questions to Stella and Judd - Interview by Bruce Glaser, 1964 von der Radio-Station WBAI-FM in New York gesendet (zitiert nach: Donald Judd, Ausstellungskatalog Kunstverein Hannover, Juli/August 1970, S. 60)

2) Werner Haftmann: Malerei im 20. Jahrhundert, Bd.1, 1.Auflage 1954, (zitiert nach der 6. Auflage von 1979, Prestel-Verlag München, S. 18)

3) Ebda.

4) Don Judd: An Interview with John Coplans, in: Don Judd, Ausstellungskatalog Pasadena Art Museum 1971, S. 25

5) Questions to Stella and Judd, a.a.O., S. 58

6) D. A. Robbins: An Interview with Allan McCollum, in: Art Magazine, Okt. 1985, S.41 (zitiert nach: Anne Rorimer: Allan McCollum - Systeme ästhetischer und (Massen-Produktion) , in: Kunstforum International, Köln 1994, Bd. 125, Jan./Feb., S. 137)

Bildnachweis:

Donald Judd: Untitled (Stacks) 1965, in: Don Judd, catalogue, Pasadena Art Museum 1971, p. 13 Donald Judd: Untitled 1962. ibid.., p. 27 Pino Pascali: II Muro Del Sonno 1966. Museum Modemer Kunst Wien